‘Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?’

‘To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.’

‘The dog did nothing in the night-time.’

‘That was the curious incident,’ remarked Sherlock Holmes.’― Arthur Conan Doyle, “Silver Blaze”

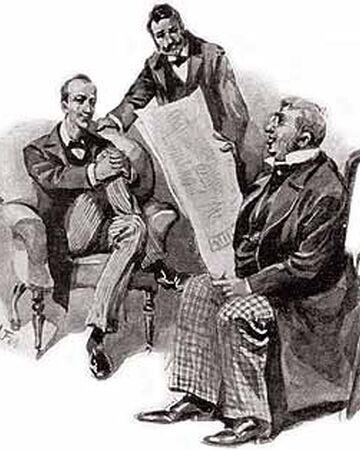

Things might not always go as planned, but there is always a reason why things happen. A whydunnit is a search for causes in order to understand the effects. Doyle wasn’t very concerned with motivation (most his criminals act simply from greed or anger), but he was a master of the art of finding interesting ways of framing events so that even things which were normal parts of life could seem strange and mysterious until Holmes unravelled them for the audience.

Strange happenings, people acting weirdly, unusual requests – these were all common ways a Sherlock Holmes whydunnit started, and the audience was then carried on a quest to find the reasons for these bizarre events and the more sinister causes which often lay behind them. By following the trails of logic, and backed up with his encyclopedic memory, Holmes was able to match result with action and often bring criminals to justice despite their elaborate schemes.

A typical whydunnit looks a little like this…

Introduction (15% or less of the story, 900 words in a 6000 word story)

- The main detectives are introduced in an interesting way which shows off their personalities. Often the detective shows off their incredible abilities by doing something that amazes the audience and other characters.

- A new character with a problem (hereafter called the “innocent”) appears before them and the main detective character shows off their detective skills by guessing information about the Innocent.

The Situation (35%, 2100 words)

- The Innocent tells the detective characters about their problem. The innocent tells them the details of what happened which lead them to coming to see (or calling for) the detectives.

- Something strange has happened to the Innocent and the reasons for this strange event will be revealed to be linked with a crime as the detectives investigate. The strange events are usually the result of a) a crime being hidden as it occurs, b) a crime being covered up after the fact, c) the Innocent being tricked into being part of a crime without knowing it. The crime can be murder, but is usually robbery or theft of some kind.

- Regardless, the Innocent will tell the detectives their story, which will include all suspects (although they may be under fake names), the important details of the events they’ve experienced, and a few important clues (which they might not realize are clues and just think are details). The detective will catch these clues, but probably won’t put them together or mention this to the audience. The clues should be worked into the story in such a way that they don’t stand out as being clues and fit in with the rest of the Innocent’s story unless the audience pays very careful attention.

The Investigation (20%, 1200 words)

- The detectives will take action to help the Innocent, usually by going out and gathering more clues or information.

- If there’s not a lot of information, then we might follow the main detective and their partner as they talk to various people involved in the case. They may interview witnesses, examine crime scenes, or collect the stories of the people involved.

- If there’s a lot of information to be gathered from various sources, the main detective and their partner may split up and then meet again later to compare notes. This is to speed up the process of telling the story by having one or both of them summarize the information they learned for each other and the audience.

- Often the case will get stranger, or there will be a twist, near the end of this phase (but not always). The most common twist is the elimination of the “red herring” cause where the most likely reason is thrown out the window by new evidence.

- At the end of this phase, the main detective (and the audience, maybe) will have the key information they need to solve the case and will often say that they know to their partner. (But not tell the audience what they’ve figured out.)

The Reveal (30%, 1800 words)

- The main detective will now take steps to catch the guilty party.

- This type of story usually ends with the detective finding the criminals and forcing them to confess the real crime they were hiding behind the strange events the Innocent experienced. The end of this one can come in many flavors, but usually either a) the criminal is caught while doing the crime they were trying to cover up with the strange events, or b) the criminal tried to commit the crime but has already failed for other reasons by the time the detectives confront them. In either case, the detective reveals everything that they figured out, and the criminal fills in the missing details. Especially if the criminal has failed due to their own mistakes (or bad luck), the criminal is just so depressed they don’t care anymore, which is why they tell all.

- With the crime laid out, the audience should be able to look back now and see clearly how everything fit together in a reasonable way. There should be no magic powers, acts of god, or huge co-incidences, and everything should make sense.

- Usually, there is one last unanswered question, and in the final scene the detective’s partner or the Innocent asks it to the main detective, and the detective answers them in some interesting way. The final scene usually ends on either a final thought or (in later stories) on an amusing note to balance out any tragedy which the ending revealed with positive emotions.

While Doyle seems to have been fond of whydunnits, they are largely the least common type of mysteries and audiences don’t seem to be as attracted to them as the other two types. This might be because they usually have the least exciting endings- the detective is learning why something happened like a curious dog following a scent, and then having found the source of the scent the story just ends. Often in Doyle’s whydunnits, the criminal has already lost by the time Holmes tracks them down, and Holmes is just there to witness their tragic fall, not bring them to justice.

This is why Doyle often combined his Whydunnits with the other two types of mysteries, using strange events to lead into a whodunnit or howdunnit. Often the whydunnits which lead many of his stories are the results of distractions from real crimes or a side-effect of people doing something criminal or immoral. Cases such as the Red Headed League or the Christmas Goose are good examples of these.

That doesn’t mean pure whydunnits can’t be interesting, they can be very interesting in the hands of a skillful writer, but they can be the hardest of the three types to write well. Answering the question of why something happened isn’t as naturally exciting as revealing a hidden villain or cracking an impossible puzzle, so the writer needs to come up with an ending that’s going to get a strong emotional reaction from the audience to make it memorable.