A while back, I blogged about a Japanese story structure called Ki-Sho-Ten-Ketsu (Kee-Show-Ten-Ketsoo), which is normally presented as an alternative story structure which doesn’t revolve around conflict. I found the whole idea fascinating, especially since our normal “western” story structure is generally entirely based around characters in conflict (with others, their environment, themselves, society, etc). Finding the Ki-Sho-Ten-Ketsu (KSTK) format seemed like a great alternative, and that’s especially true since there aren’t a lot of different story structures out there.

For those who aren’t familiar with the structure, it works like this:

- Ki– Setup the situation.

- Sho– Development of the situation

- Ten– Twist or surprise on the situation that the audience expects.

- Ketsu– Resolution of the situation.

For example:

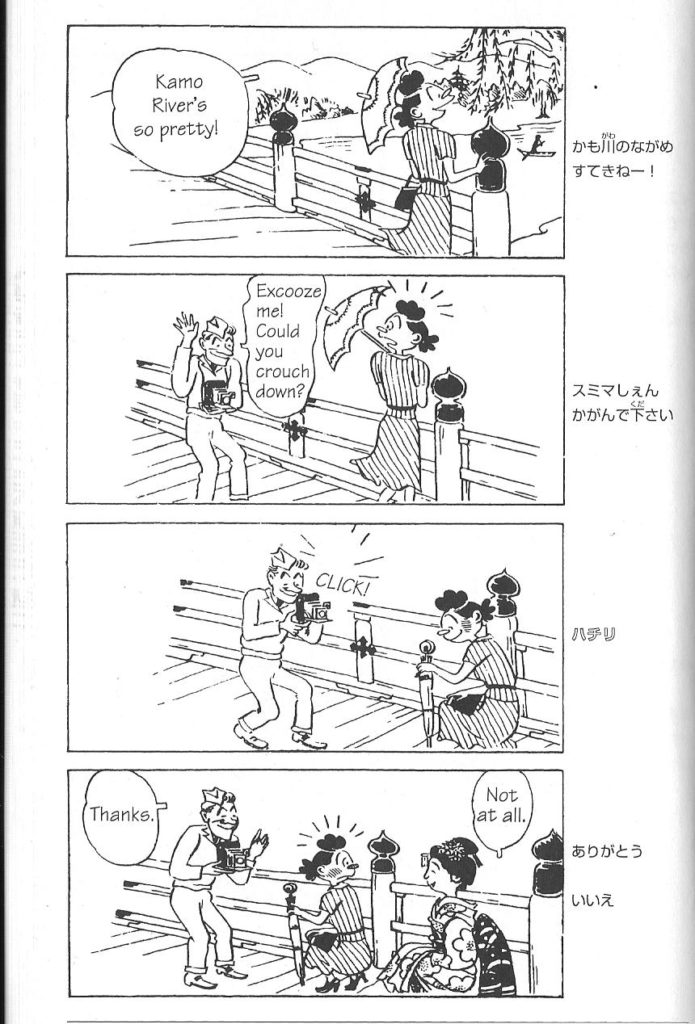

- Ki– Sazae-san is enjoying a riverside view.

- Sho– An American Soldier appears and asks her to kneel down.

- Ten– Sazae-san is pleased he wants to take her picture.

- Ketsu– He’s really taking a picture of the beautiful girl behind her.

This format was originally found in Japanese poetry, but later became “famous” as the structure used in their Yon Koma (4 Panel) gag comic books. (Their equivalent to our newspaper strips.) Some others have come to use it in different ways, but the information out there in English said that it was a structure that relied on dramatic and situational twists to produce a reaction from the audience (usually a humorous one). However, when you’re working with limited sources of information about a subject that isn’t in a language you speak, there’s bound to be some miss-communications here and there.

Having recently been able to read the fascinating book Manga in Theory and Practice: The Craft of Creating Manga by Hirohiko Araki, I have discovered that my understanding of the KSTK form wasn’t quite right.

I had believed it was a form without direct conflict, but now thanks to Araki I understand that instead it is highly flexible form where the conflict is optional because the story structure doesn’t require it. In fact, Araki demonstrates in his book that it is in fact the standard format still used by many manga writer/artists today when planning short stories and chapters of their serials. Not only that, he demonstrates how flexible the structure is.

But first, let’s make sure it’s clear what each step represents.

- Ki – In this stage, we get a character and situation, and that character demonstrates a need, usually one based on a derivative of basic human needs.

- Sho – The character makes a plan, and tries to follow a path they think will fill that need.

- Ten – The character faces an obstacle to their plan, and must figure out how to overcome it.

- Ketsu– The character is done facing the current obstacle(s) and now has either fulfilled their need or moved closer towards fulfilling it.

This structure actually conforms to the basic structure that all stories must follow, and represents a simple and universal way of looking at story.

A sample short Romance story:

- Ki– Two people meet.

- Sho– They fall in love.

- Ten– The man’s ex-girlfriend gets in the way.

- Ketsu– They overcome their challenges and marry.

Therefore, it’s no surprise that, according to Araki, most manga stories tend to follow this structure closely or loosely. He also mentions that a common variation of it is the structure of Ki-Sho-Ten-Ten-Ten-Ketsu (with the number of Tens (twists) being as few or many as needed). In fact, referring to Ten as “Twist” might be a mistranslation in this case, as it’s often more like “Dramatic Event,” “Unexpected Revelation,” or just plain “Opposition.”

You could have a dozen small Tens or just one big one, and they can take any form you’d like, as long as they keep building the dramatic power of the story.

A longer Romance tale:

- Ki– Two people meet.

- Sho– They fall in love.

- Ten– The woman’s insecurities get in the way. (problem)

- Ten– The man’s family hates the man. (bigger problem)

- Ten– The man must follow the woman to Europe and bring her back. (biggest problem)

- Ketsu– She agrees and they marry.

Also, as Araki also points out, the Ketsu phase can be moved around and take different forms. For example, in serial stories (or chapters of a book), the Ketsu might be delayed to the start of the next installment, so you end up with a structure like:

- Part A: Ki-Sho-Ten-Ten

- Part B: Ketsu-Ki-Sho-Ten

- Part C: Ketsu-Ki-Sho-Ten

- Part D: Ketsu-Ki-Sho-Ten-Ketsu.

In this case, the Ki in part B-D is actually the “new normal”, not a complete reset to zero. The Ketsu is producing a “new normal” or “new state” which the characters are at, and then the next round of buildup (Sho) begins towards a dramatic situation. There is always an upward building of dramatic momentum as the story progresses, so that each cycle tops the one before it. This way, the reader is always wanting to read the next installment/chapter to find out how the situation resolves, and is kept focused on the story until the end.

Specifically in Manga, the pattern tends to work like this:

- Ki– Introduce the characters and situation.

- Sho– The situation develops/the characters pick a goal.

- Ten– A dramatic event (or series of dramatic events) happens. (There can be more than one Ten)

- Ketsu– The dramatic event(s) resolve to create a new situation.

Or, they look like this (especially during multi-chapter battles or multi-part stories.)

- Ketsu– The dramatic event(s) of the previous chapter resolve to create a new situation.

- Ki– This new situation and it’s characters are established.

- Sho– The situation develops/the characters pick a (new) goal.

- Ten– A dramatic event (or series of dramatic events) happens. (There can be more than one Ten) The Chapter will end on a Ten beat, leaving the events unresolved until the next chapter (forcing the reader to read the next chapter to find out what happens.)

So, for example:

Opening Story Arc Chapter:

- Ki- Ninja Bob and Ninja Sue are facing off with Evil Ninja Red over a Ancient Ruby.

- Sho- Bob and Sue try to convince Red to join them.

- Ten- Red counters by offering to let them join him instead. (Event)

- Ten- When they refuse, Red reveals he knows Sue’s dark family secret and says unless she joins him he’ll reveal it. (Oh no! Bigger Event)

Middle Story Arc Chapter:

- Ketsu– Sue says she doesn’t care, she won’t betray Bob.

- Ki– Bob and Sue resolve to fight Red, who is clearly not going to give up peacefully.

- Sho– Bob throws a smoke bomb while Sue attacks!

- Ten– Red dodges Sue’s attack. (Event)

- Ten– Red counterattacks Sue, sending her flying. (Bigger Event)

- Ten– But Bob came in for a surprise attack behind Sue. Red is caught off guard! (Biggest Event)

End Chapter:

- Ketsu– Red is caught by Bob’s attack and left injured and unable to fight.

- Ki– Bob rushes to Sue and finds her dying of a sword wound.

- Sho– Red tells Bob the Ruby can save Sue.

- Ten– But the Ruby will be destroyed in saving her! (Event)

- Ten– Not wanting Sue to die, Bob sacrifices the ruby. (Bigger Event.)

- Ketsu– Bob and Sue return home to their ninja village to face their master. (And a new series of events!)

Finally, one last advantage of this story structure is its flexibility of length. You can make a KSTK story as long or short as you want, and obviously have a overall KSTK structure with the chapters within also having mini KSTK structures. The above Romance could be a short story, or it could be the root structure of a whole novel, depending on how you want to let the story unfold. It is especially good for stories where character or setting have a greater focus than plot, because it can allow those elements to play out while still having what the audience will recognise as a story structure underneath.

And, of course, not all the dramatic twists have to be ones based on conflict, and I now know and appreciate. 😊Live and learn!

Have fun experimenting with this structure, and read Araki’s book if you get the chance, it covers a lot more things than just this, many of which you might find useful.

For more on writing manga and anime plots, see my book Write! Shonen Manga. Available on Amazon and wherever online books are sold!

Rob