Silent films were an international language. Taking advantage of the fact they had no natural soundtrack, they were designed and produced to be understood through purely visual storytelling. Even when dialog cards were later introduced to add key pieces of dialog, the core of the films were still visual. This allowed them to be watched and understood by audiences the world over, or world audiences which lived right next door, since this was the great age of immigration and your neighbour may not speak the same language you did.

When these silent films were exported to other countries, they were adapted to the local customs, and in the case of Japan they took on narrators who were there to help the audience with the points of the film that local audiences might not understand. These narrators, called Benshi, would introduce the film to set the story and context, and then narrate the story as needed for the audience to help them get over jumps or occasionally missing pieces of film. While in the Western tradition, organs were used to accompany silent films for music, the Benshi worked alongside traditional Japanese Kabuki orchestras to produce a very Japanese movie-going experience from 1910 until the mid-1930’s. It worked so well this system was also adopted into early Taiwanese cinema, with the narrators called Benzi.

The Benshi also shaped Japanese cinema, as the producers of Japanese films of the time knew that a Benshi would be there to narrate their films and so they started to script their films with the expectation that the Benshi would not only narrate, but do all the voices for the characters (of both sexes) as well. This made the Benshi truly part of the drama, and different Benshi became major stars based on their styles of acting and narration. People would even go to see the same film again if narrated by a different Benshi because it was said that in the hands of a different Benshi the same film could become a comedy, a romance, a thriller, or take on different levels of drama as the Benshi would add their own improvisations and style to the film’s story. You might even say that the Benshi became the reason people went to see the performance, and that the films themselves become a backdrop for the Benshi!

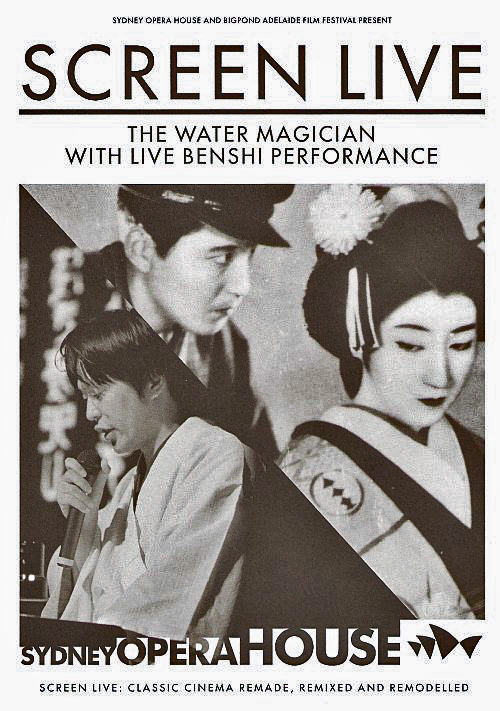

According to Wikipedia, “in 1927, there were 6,818 benshi, including 180 women.” This was likely their peak, as it was around this time that the first American “talkies” appeared and sound was introduced to movie-going audiences. So, while Benshi did continue on for a time as translators for foreign films, their services were less and less required, and they slowly became a rare cultural tradition. Today, there are still Benshi like Midori Sawato who do performances when silent films are played in art houses and on special occasions, but they are a rare experience. Here is a series of short clips showing a Benshi in action from the above performance at the Sydney Opera House:

I personally find Benshi fascinating as a concept, and think it would be amazing to watch one perform, although technically I already have. Back when I was the president of Anime London in the 1990’s a group of us would meet on the second and fourth Monday of every month and watch anime from my fairly large (at that time) collection. One of the shows we watched was a series called Macross 7, and I had the whole series on videotape with only one problem- it was still in Japanese and wasn’t subtitled after the first two or three episodes. This was in the days before internet video was really big (or possible in any quality), but I did manage to find translation scripts for subtitlers to use online. However, I didn’t have the equipment or ability to subtitle all 49 episodes of Macross 7, so what to do?

My not-all-that-innovative solution was to become an audio subtitler, and read the scripts alongside the dialog while the rest of the group watched the show. (Holy Benshi, Batman!) However, after a few episodes one of my friends, a talented young man named Glenn Jupp offered to take over audio-titling for me for reasons I’ve forgotten. (I think I couldn’t do it one week for some reason.) Glenn was a natural Benshi, and would have done these Japanese masters proud. I never did it again because Glenn spent the next 44 episodes giving Macross 7 his own personal spin by doing his own inflections to all the voices, and showing incredible timing and dramatic flare. It worked perfectly, because Macross 7 is an over-the-top mecha anime musical, and having a wild dramatic reading of the lines just fit perfectly.The highlight of each meeting became watching Glenn perform, and while new members to the club took a bit to get used to our unusual way of doing things, they soon came to appreciate Glenn’s talents.

It made watching Macross 7 a unique experience that took the show to a whole other level, and even today I can’t watch it subtitled without hearing Glenn’s voice narrating the character lines. (“Listen to my song!!!”) The day we finished the series, I think we gave him a well-deserved standing ovation, and when they released some direct-to-video episodes of Macross 7 we got scripts and asked him to narrate once more. Watching it without Glenn just wouldn’t have been the same, and I can appreciate how audiences in Japan felt about their Benshi, because Glenn was ours.

Arigatou, Jupp-san. You would have done the masters proud!

Rob