There are a few less common manga genres that probably deserve more attention than they get, and one of these is the Exploratory Manga.

Now, when I say “Exploratory Manga” you might think I’m talking about stories like Star Trek, Indiana Jones, Uncharted, or other adventure stories where the hero is going into strange new worlds. However, while those do have elements of exploration, I would classify those more as a type of adventuring story.

Instead, what I call Exploratory Manga (and anime, and light novels) are stories where the whole purpose of the story is to explore a setting and the characters are basically just guides leading the audience through that setting. They might be knowledgeable guides who know the setting well, or they might be characters who have entered this setting at the start of the story and now explore it along with the audience, but their function is to be a guide for exploring the setting.

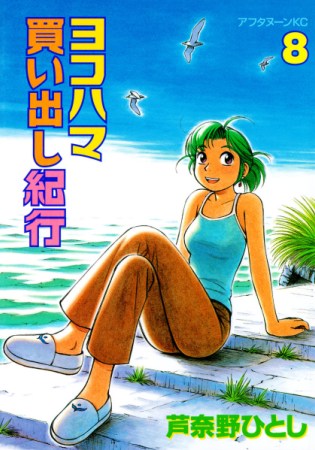

So, for example, maybe the main character is exploring the world of food. In that case, they might explore the world of deserts (Kantaro: The Sweet Tooth Salaryman), or wine tasting (Drops of God), restaurant culture (Oishinbo), or any of a host of other food-related topics. All of which are stories where the focus is mainly on a character working their way through the cultures, sub-cultures and wisdom that surround food culture in Japan and abroad.

In these stories, there is (often) no real overplot or goal for the main character beyond gaining knowledge and understanding of their chosen topic. Maybe they want to improve their skills in their chosen area, or maybe they have someone they want to surpass, but either way, the real star of the show is the setting they’re exploring. The character is just a vehicle for going though that setting like a car in a theme park ride.

These lead characters usually have little to no character arc beyond maybe going from inexperienced in the ways of the setting to experienced, and maybe not even that in some stories. That is because the character is not the point and is only there to be a viewpoint for the audience to come to understand the world around the character.

Because of this, these stories are usually fairly low impact, and often (but not always) have little to no conflict in them. These aren’t Hero’s Journeys, but stories where a character is simply learning and exploring a world the creator finds fascinating and wants to share with the audience. The conflict in the stories (if any) is often speed bumps instead of obstacles, and is there to add a light touch of drama at most.

A good example of this is the manga Heterogeneous Linguistics, which also demonstrates that these kinds of stories don’t even have to be set in the real world. In this story, a young graduate student from a human-dominated continent in a fantasy setting travels to a continent dominated by primitive monster races in order to continue his professor’s work of studying their languages. The whole story is about him and his young wolf-girl assistant living among primitive peoples of the continent and figuring out how each communicates. There are no battles, no action, no romance, and little to no conflicts except for the occasional linguistic challenge or miscommunication.

And yet, the story itself is unique, fascinating, and one of my monthly favorites.

Heterogeneous Linguistics also demonstrates one of the two main patterns these stories tend to follow – the learning lead, or the observing lead.

In this case (the learning lead), the main character is encountering and learning from a series of other characters who are part of that world. In these stories (and in Exploratory Manga, it’s often about a series of short stories, not long epics – they’re almost anthologies), each new part of the setting the character explores has a guide character (or characters) for the main character to interact with. The main character learns from each of them, and then moves on more knowledgeable than they were before they met the “guide.”

Other examples of this pattern are Laid Back Camp, Yotsuba&!, Super Cub, and most of these manga.

The other variation is the “observing lead” stories. In these stories, the main character really is just an observer, and the real story is about the other characters they meet and encounter. One example of this is Wandering Witch: The Journey of Elaina, where the main character is a young witch on a journey to explore the fantasy world they live in. Elaina is just there to meet other characters who represent the different aspects of the setting world and the stories are really their stories, not hers. But, through each of their stories, we learn something about the setting they all live in.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because this is also the pattern for old American cowboy westerns (and Japanese samurai movies) about the action hero who wanders from town to town meeting new people and finding trouble. However, in this case, there’s usually little to no “trouble” and the focus of the story is more on slice of life and daily life.

To give a comparison, in an action/adventure cowboy western story about a town well, the lead character would wander into a town where the local well has run dry and a local rancher is using the only remaining other water source as an excuse to rule the town with an iron fist. The lead character would get to know the local suffering townsfolk and their problems. And then, when the tyrant tries to kidnap and marry the local saloon owner’s daughter, the lead would jump into action and work his way through the tyrant’s men with his six-shooter until the tyrant was dead and order was restored. (Before riding off into the sunset, to the next town.)

However, in an exploratory story about a town well in the old west, the lead character would wander into town looking for work and find the local well had run dry. Then he’d meet the local doctor, who thinks he can solve the town’s water problem through finding new underground water sources and end up getting hired to help him. As they work to solve the problem, he would learn about the doctor’s motivations and the doctor would talk about the relationship the townspeople have with water. Finally, after some effort, the doctor would find a way to use their theories to tap the water and return the town to normal. The lead would then go on, having learned about the relationship between life and water in the old west.

As you can see, these are very different stories, despite the same premise. One is about the lead restoring order through action and violence, and the other is about the lead meeting a character who acts as a guide through a piece of the world they live in, before themselves moving on to explore another piece of the setting.

This type of story is largely possible because the Japanese use the Ki-Sho-Ten-Ketsu story structure which doesn’t require conflict to work, but only requires that progressively interesting things happen. Then, following the Japanese approach of watching interesting things interact, the author only needs to bring the main character in contact with the characters or parts of the setting they find interesting, and the story naturally flows from their interactions. There can be conflict, but it isn’t needed, and most often the story is built on learning rather than drama.

Which brings us to the question – what makes these stories work? As I’m sure to some of you this sounds like a dreadfully dull type of story.

Well, as I wrote about some time ago, there are five things readers get from stories, which can be remembered from the mnemonic SPINE – Skills, Perspective, Information, Novelty, and Emotion. And, even without conflict, these stories can offer pretty much all of those things to audiences to keep them hooked.

Skills: In some exploratory manga, they’re literally teaching the audience how to do things, like cooking or camping.

Perspective: Often these stories offer a new perspective to the audience about some aspect of the setting or the real world. For example, why do people love stamps so much? Or why are some people obsessed with fishing? These stories give us a glimpse into parts of our world we don’t normally interact with, or parts of other worlds which can give us new reflections on our own.

Information: Exploratory Manga are all about sharing information. Usually they’re sharing some combination of Information and Perspective as their main driver. The audience is learning as they’re being entertained.

Novelty: Through offering Skills, Perspective, and Information, these stories let the audience explore a new world they haven’t seen before and come to know more about the world they live in. These stories are trying hard to evoke a sense of wonder in the everyday and mundane, and often use their art to bring that wonder to life.

Emotion: Sometimes these stories have drama, especially if they’re about the characters the lead meets as they travel/explore, but most often these stories evoke positive emotions like curiosity, fulfillment, happiness, and humour. They’re about the joy of learning about the world, a joy which many people have often forgotten as they have aged. Or, they might be mono no aware stories where the audience is brought in touch with complex and melancholy emotions connected with the passing of time.

Using these ways, and often paired with appealing art and characters, the creators delve deep into the setting of their stories and teach us about those worlds while expanding our own.

Thoughts on writing these stories:

I have noted that these stories tend to be written by and for older and more mature audiences. This makes sense because you have to have life experience to write one of these stories well, and most younger creators (and audiences) don’t have the time or patience for these stories. They want something with a stronger emotional impact and prefer more visceral works. That’s why many of these stories would be classified as Gekiga (dramatic pictures) not Manga (foolish pictures) and are usually found in publications for older audiences. (See the works of Jiro Taniguchi for examples.)

That isn’t to say that these can’t be appealing to younger audiences, and in fact you could easily make the argument that a number of Miyazaki’s films are actually Exploratory Anime, like Kiki’s Delivery Service, for example. However, it takes a light touch to make them work well for a younger audience, so even there the creators are usually older and more experiences artists.

Instead, for younger audiences, you usually see elements of Exploratory Manga incorporated into other manga genres like Shonen Battle or Romance. Where they take the exploratory elements and use them to help build and flesh out the world of the characters. A good example of this would be Yowamushi Pedal (“Weakling Pedal”) which is primarily a sports manga about cycling, but delves deep into different aspects of the amateur cycling world in Japan. In fact, many Sports Manga make heavy use of Exploratory Manga approaches to teach their audiences about the sport in between the competitions. The main difference being that at the end of the day the sports manga are about the characters, battles, and competitions, while their exploratory manga counterparts are about the setting first and foremost.

The other way these types of stories are often made to appeal to younger audiences is by making them funny or humorous. Everyone likes to laugh, and humour is a natural way to bring out the appeal of the story events and setting. Thus, commonly these are written like slice-of-life stories where the character ends up in some humorous situation by the end of the story, or has a series of amusing (but rarely laugh out loud) events happen to them. This isn’t a sitcom, but a gentle and fun reflection of reality that is often (but not always) bathed in sunshine.

You also see this type of story in hobbyist and profession-related magazines in Japan, where they often function as basically a serialized “for dummies” guide for people new to the hobby. In this case, they’re usually built around appealingly designed characters having amusing slice-of-life experiences related to pursuing the hobby or profession in some form. This can be as simple as playing collectable card games or model kit building, or full on professional activities like voice acting or being a country veterinarian.

Lastly, I should mention that these stories are largely possible because the Japanese are producing them in comic book form. The comic book form allows images and pictures to make complex or sometimes dull subjects lively and interesting in ways that text struggles to. Yes, there are Exploratory Light Novels that exist, like Kino’s Journey but I would argue they’re possible because the audience is already used to these types of stories from manga. Also, Kino’s Journey is still mostly about the characters the lead meets and their dramatic lives, as opposed to a story about the intricacies of stamp collecting which would be dull as dishwater without visuals to help prop it up.

This isn’t to say that you couldn’t do this type of story as a prose novel or story collection, but it would take a lot of skill to do well. Stephen Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town might qualify, and I’m sure there are other master writers who have done versions of this, but it usually takes the form of some type of literary fiction in English which has an older audience and not a lot of mass appeal.

Final Notes

When North Americans write about setting, they almost always turn it into a mystery or literary fiction of some kind. Most often, it’s a character trying to uncover the truth about some event, and to do so they must come to understand a new environment or world they (and the audience) weren’t familiar with before. This is a good way to do it because the mystery frames the exploration and gives the writer an conflict-based reason to examine a setting that often doesn’t want to be examined by the lead character.

Exploratory Manga bypass this approach and instead throw open the doors of the world and invite the character and audience in for tea. The reader isn’t an intruder uncovering dark secrets (although that’s not off the table), but instead a welcome guest invited in like a beloved grandchild to experience the hidden corners of their grandparent’s ancient home. The joy of exploratory manga comes from discovery and learning, not from violently ripping back the curtains to expose the truth to sunlight.

Exploratory stories are driven by love, not fear or hate, and a sense of curiosity that often takes the reader back to their youth. They reflect on the human condition, and gently make us consider our own lives in a non-confrontational way or expand our horizons to understand our world a little better.

They are about the joy of interacting with the world around us, and reminding us that we are part of a vast web of connections. Never alone, and always linked to the greater world we live in.

I’m really just scratching the surface of this topic, but I wanted to think about it for a bit, so I wrote this post as a way to organize my thoughts. This is one the aspects of manga I find fascinating because it’s literally a genre that doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world except maybe Europe and some online webcomics inspired by the Japanese stuff. However, the Japanese are the kings of it, and through studying it we can learn a lot about both Japanese and Western concepts of storytelling.

So, what are your thoughts? Do you have some favorite Exploratory Manga (or anime, or stories) you love or would like to recommend? Leave a comment below!

Rob

Update:

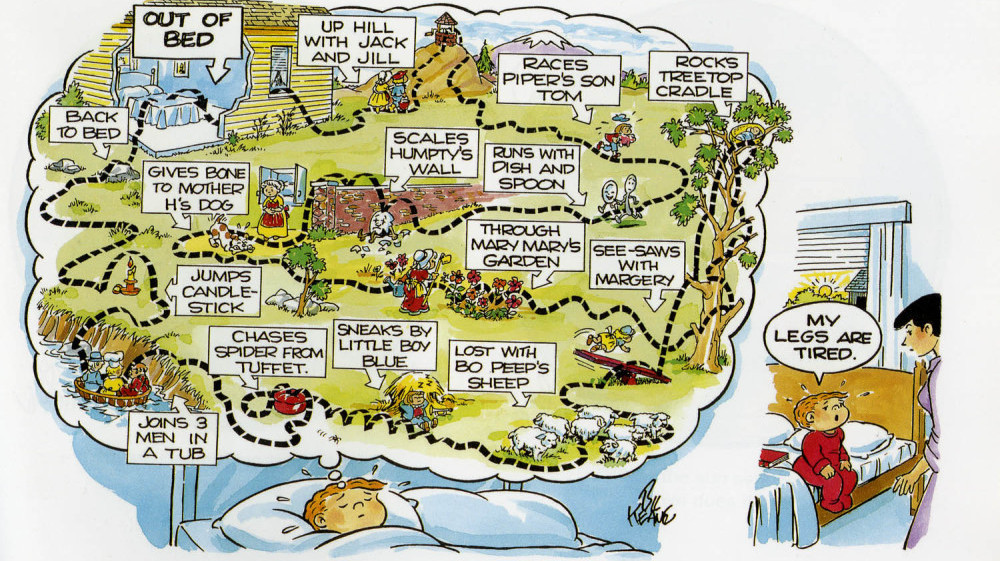

As my friend Don pointed out in the comments for this post below, Americans did at one time do stories similar to this in newspaper strips, but they were very short. The ultimate example of this is probably the Sunday color comics where Bil Keane took us on adventures with little Billy.

In this Bil Keane Family Circus, Jeffy wanders the neighborhood in dreams.

These were popular enough that Bil Keane did many of them, and it was a neat way to put a whole day’s worth of youthful explorations and adventure into a single panel. You can read more about them here.

Another example of these, back in Japan, is that there’s an actual long-running TV series that uses this concept in the real world – Somewhere Street. Each episode is basically a walking tour of a city somewhere in the world and it’s environment. Something like a live-action version of Billy’s Adventures. The ones I linked to on YouTube are from NHK World and dubbed in English. Try watching some, it will make you want to start travelling!

Hmmmm…. we USED to do comics like this in N. America…. newspaper strips mostly. I think “Mark Trail” is the only one still running anyone would have heard of; and it sort of bebops between this and an straight adventure strip…. although the adventure is usually weird and detached in a “stream of consciousness” sort of way. I think you can argue that a lot of the “family” strips are this. (Or are TRYING to be this.) Stuff like “Family Circus” or “Gasoline Alley,” and the thing that makes them feel like comic zombies (AND makes them targets for Josh Fruhlinger) is that they’ve stopped presenting new aspects of their world and just meander through the old, used tropes and conventions. They’re exploration stories that aren’t exploring any more….

I think it worked best as a newspaper strip ‘cos N. American entertainment has always been more action packed and sensationalized, but a daily strip doesn’t require a lot of commitment. We can painlessly spare 27 seconds to eyeball the latest instalment.

The Brits flirt with this sort of comic…. mostly in their old school girls’ comics. They were obstensively drama, but in a lot of cases the drama was so grounded and low key it felt more like a discussion into the psyches of the participants. (Exploring the realms of the mind and the heart maybe?)

Don C.

You make some good points, so I’ve added a link to the Family Circus in the post above, because that’s exactly what that is. It’s just the Japanese take it to the next level. Maybe the Japanese are culturally more patient than Americans, so they’re able to enjoy more “peaceful” forms of art and entertainment. Hell, they’re able to sit through Noh Drama, so there must be something to this! (Although I know most modern Japan don’t want to sit through Noh Drama either!)

Your comment about the Brits is kinda fascinating. Yes, you could do this kind of story where you’re exploring the psyche of a person instead of a place. I hadn’t really thought about that before. In that sense, I suspect a bunch of what we call Literary Fiction is exactly this – low-key exploration stories of the inner human condition. Women seem more drawn to these stories than men, so I wonder if there’s a gender difference there, and that’s why it’s the British girl’s comics where you see it showing up.

Well…. nowadays anyhoo. Not too long ago this sort of thing was how N. American sitcoms (and Canadian dramas) were done. Again; leaning more towards traditional (if not low-key) conflict. It may tie into Scott McCloud’s discussion of western comics being event driven, with the story moving from event to event to event; whereas the Japanese do a lot more scene setting with their comics.

Some of that could be inertial based on marketing assumptions that girls like stuff along those lines…. Although one of the reasons female fans tend to prefer drama may have something to do with females thinking more in terms of context than males, which is what drama is all about. Once again Japan provides the confounding variable when you think how much action stuff produced there in the 80’s was heavy on the soap opera aspects. Stuff like Gundam, Macross, Ideon, Area 88…. Although a lot of THAT was thought to be cross pollination; that the action stuff appropriated it from the josei comics and cartoons of the day as a way to freshen up the old tropes.

When it comes to the nerdly arts here in N. America I think the 80’s were good and bad. They saw an expansion of what could be done, but they also saw a LOT of compartmentalizing, so we lost out on a bunch of hybrid stories that places like Europe, Japan and G Britain saw during that time.

Don C.