For some writers, the idea of plotting out a story is a nightmare.

To them, it just takes all the fun out of the writing.

For these people, known as Pantsers (as in “Fly by the Seat of your Pants”) or Discovery Writers, the whole point of the story is to go on an adventure with their characters and experience the story as it plays out with themselves as the story’s first audience.

So, planning the whole thing out first would defeat the purpose of writing the story in the first place.

However, this approach to writing comes with a cost.

While pantsing can produce stories which feel more fresh and original because they aren’t tied to some plot formula, it can also produce huge amounts of frustration. False starts, unfinished books, writer’s block, and expensive editing bills are also a common part of being a pantser.

It’s enough to make many of them want to quit writing.

But, what if there were a few ways a pantser could skip all that frustration while at the same time not having to go down the “dark path” and becoming one of “them” – a plotter?

This article is going to look at a few different ways to do exactly that – let pantsers have their discovery cake and eat it too!

Method #1: The Character Method

In this method, the writer doesn’t plan their story, but does plan their characters.

They take some time to write out character information sheets and make notes about who the different major characters are in the story before they start writing.

At the very least, for each character they write down as much as they can about…

- Each character’s goals

- Each character’s motivations

- Each character’s personal flaws

- Anything about the character’s history they can come up with

This doesn’t have to be pages or books of information, but anything the writer comes up with can help a lot because it will all factor into the story in some way.

Another suggestion to avoid a lot of editing later for consistency of character is to do an “interview” exercise with the characters before the writing begins. This is where the writer takes a list of character questions they find online, or makes some questions specifically related to the issues or themes of their story, and then “interviews” their characters in the first person on paper.

It looks a little like this…

Q: How do you feel about forgiveness?

A: Forgiveness is for the weak. Nobody ever forgave me for the mistakes I made in my life. Not my ma, or my pa, or my teachers. If I made a mistake, they punished me for it and I learned. It’s punishment, not forgiveness that drives people forward. Fear of it is a great motivator, and it makes your head clear. Forgiveness is something that religious types talk about, but that’s just them hiding their inner weakness because…

And on it goes, in a free-flowing style where the writer lets the character “speak” and answer however they want, and isn’t afraid to let them go off on tangents. They just let them say what they have to say on the subject, whether it’s a few words, or a small book.

This way of exploring the character’s relationship to the themes of the story will hopefully reveal the voice and manner of the characters before the story starts, and let the writer start to think about how all these characters will relate to that theme and come together in the actual story.

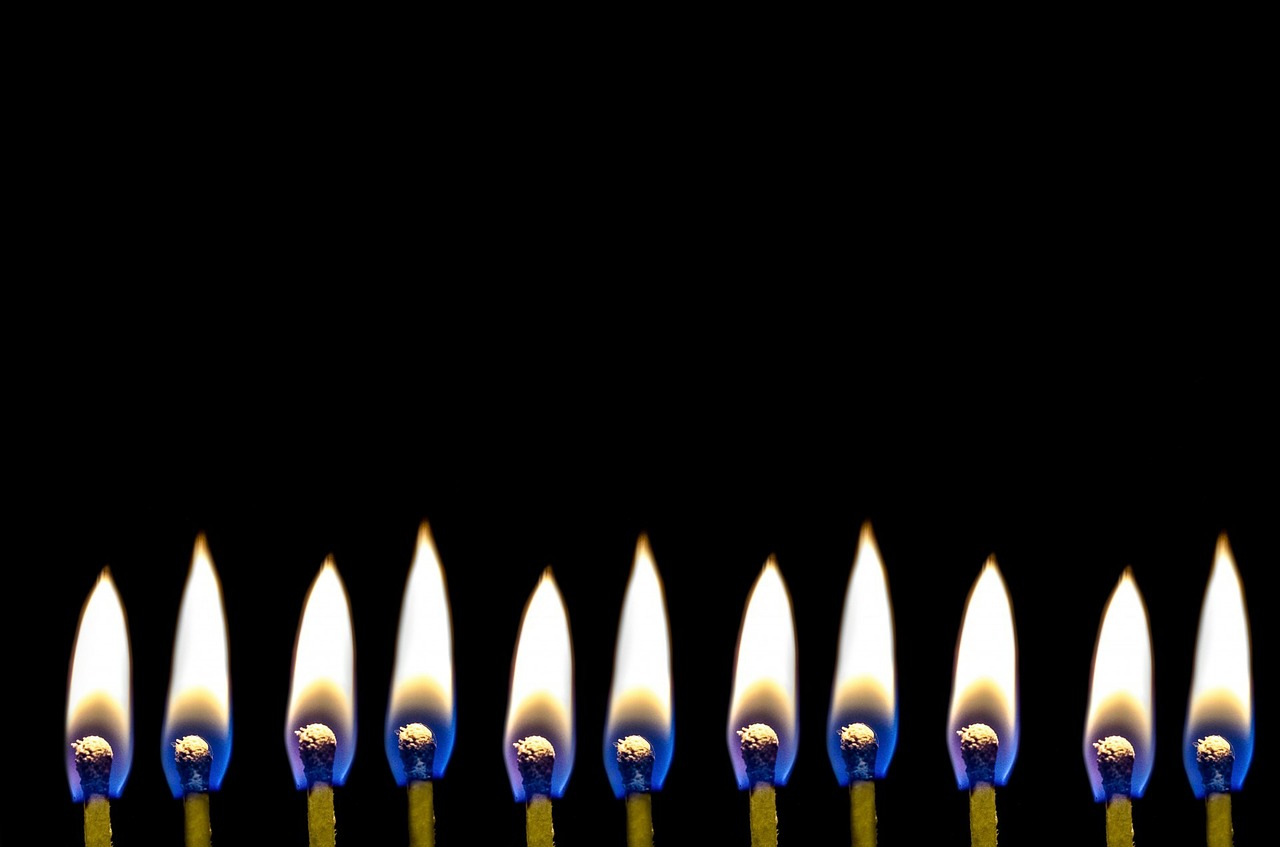

Method #2: The Forty Fires Method

In this method, the writer sits down and brainstorms at least forty different events that could happen in their story.

Why forty? It can really be any number, but it really needs to be enough to stretch the author’s imagination a little and give them enough time to get creative. Thirty might do, as would fifty or sixty, but forty is a good number to shoot for.

The idea here is that the writer looks at their story idea and then comes up with forty different big and small events that could happen in the story before they write it. Each one should be a bullet point of one or two sentences in length. They might be based on the genre of the story, the characters involved, what the writer would like to see happen, interesting ideas, or whatever else they can come up with.

Once they have those forty ideas, they can do a couple things with them.

If they see some ideas that they like and jump out at them, they can take those ideas and note them down in some kind of order, put them into spots in the 3-act structure, or even start to turn them into chapter outlines.

However, for most pantsers, that would probably be more than they want.

Instead, the best thing to do is to just take that list and put it away while they go write the story.

And then, when they find themselves getting stuck or facing writer’s block, they can just pull out the list and go over it, looking for ideas to get themselves moving again. As that’s what this list is really for, not just to think up some possibilities for the future, but to re-ignite the fire in the story when things are starting to burn low.

It’s a list of ideas the writer passes to their future self to use when they need it and to help guide the story without forcing an outline on it or limiting the writer’s creativity.

Method #3 The Timeline Method

In this method, the writer creates a timeline of events instead of a plot and uses that timeline as a rough guide.

On the surface, this might sound like plotting the story out, and if you get detailed enough it can become that, but it doesn’t have to be. Instead, this method is about making a timeline of events big and/or small that help to guide and shape the story without getting into the weeds.

For example, a timeline for a fantasy story might look like this…

1203 – Empress Lilula Ascends to the throne.

1204 – A war breaks out with the neighbouring kingdom of Mistonia.

1206 – Mistonia’s royal family is killed during the siege and the war ends with Mistonia joining the empire.

1213 – Empress Lilula goes into seclusion citing health issues.

1215 – Empress Lilula dies, replaced by her brother Emperor Desmon

1218 – Emperor Desmon goes into seclusion, leaving his concubine Lady Vass effectively ruling the empire as the sole speaker for the Emperor.

…And so on.

Once this dry historical record is concluded, the writer then acts like a real historian and weaves a story around the major events to explain why they happened when they did and how these events are connected to each other. Instead of a plot outline, the timeline acts as a set of guideposts that give the writer things they can play with and questions to answer as they write.

In the above timeline, why do the rulers of the empire keep going into seclusion? How is Mistonia’s fall connected to the fate of the imperial leaders? How did a concubine end up in charge?

There are many different ways those questions could be answered and the story could play out, and the timeline acts as a guide for creating the “true” history which lead to these events as the writer explores and has fun in the setting.

Method #4: The Race to the End Method

In this method, the writer figures out an ending before they begin, and then discovery writes the events which lead up to that ending.

This approach is similar to the timeline approach, but keeps thing down to a single event – the ending of the book itself (or series of books). The writer goes in knowing roughly where it all goes, but not how it reaches that ending, and then backs up far enough to give themselves room to explain why the story had the ending it did.

Of course, some people might see this as against the whole point of “discovery writing” and not knowing how it will all turn out. But just because a writer has an ending in mind when you start, doesn’t mean the story has to end up exactly in that place. The story might change and evolve as it goes to end up with a “better” ending that’s similar to the planned one, but only in a general sense.

Method #5: The Theme Method

In this method, the writer sits down and thinks about the theme of the story, and then uses that theme as the guiding principle for the story as they write it.

Sometimes just knowing the theme of a story (“motherhood,” “friendship,” “truth”) or knowing the thematic statement of a story (“motherhood is a lie,” “friendship conquers all,” “truth is relative”) is enough to let a writer find their way to the end of the story. A strong, clear theme connects all of the characters, events, situations, and even the setting of a story together and makes the parts of the story work together as a single whole.

When challenges come up in writing the story, the writer just needs to look back at their theme and ask how what happens next reflects that theme in some way.

When thinking about the theme, the simpler and more primal theme the better. It has to be a theme that most members of the audience can relate to and understand. So, something complex like “truth is relative” can make for a hard theme to work with for many writers, and can be challenging to convey to the audience well.

On the other hand, “friendship conquers all” is an easy theme to weave into most narratives. (Which is why it’s a theme which is used constantly, especially in young adult fiction for boys.)

In Conclusion

Whichever method you use to plan your stories that works is the right one for you, but there’s no harm in trying different ones and see if they work for you. Even with pantsers, there are more and less efficient ways for each writer to write, and a good writer is always looking for a way to up their game.

The only type of pre-planning which is best to avoid is detailed worldbuilding. A little bit of general worldbuilding is fine, but detailed worldbuilding is the quicksand pit of dreams which produces nothing but misery for the writer who goes down that path. Most of the details will never end up in the story, and the audience doesn’t care about the setting except as it relates to specific characters and their lives. As a result, detailed worldbuilding is a waste of time better spent writing fiction instead of notes.